Carbon Markets? What Are They?

As the drive to stop the rampant global climate crisis accelerates, there is more importance placed on carbon markets to achieve net-zero greenhouse-gas emissions.

The carbon market is a market where we trade carbon emission allowances. It is a market-based approach related to emissions trading, which aims at controlling pollution by providing financial incentives for reducing emissions of companies and enhancing decarbonization. In this scheme, authorities allocate or sell a limited number of permits that allow the discharge of carbon emissions over a set period of time. Companies are required to hold permits that are equal to their emissions, and in case they want to increase them, they need to buy permits from others who are willing to send them. Those limits imposed on carbon emissions help to ensure that the environmental goal is met, and trading these limits provides flexibility for companies when it comes to complying with the sustainability regulations.

Carbon markets focus specifically on CO2 emissions, but there are other markets as well, for example, SO2 markets, that help to cut down the sulfur dioxide pollution responsible for acid rains.

Can Carbon Markets help fight climate change, or will they become a loophole for polluters?

Rich Gilmore, the CEO of Carbon Growth said:

“Unlike cryptocurrency or Bitcoin, the carbon market is underpinned by existentially important intrinsic demand for the end use of the product – a carbon credit exists to be retired. Our view is that there is a stable and growing demand for carbon credits to be used as an emissions reduction tool.”

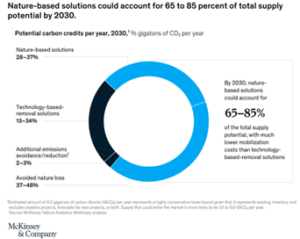

Under Article 6 of the 2015 Paris Agreement on climate change, if one country pays for carbon emissions to be reduced in a second country, the first country can count those reductions towards its own national targets. If executed correctly, international emissions trading could almost double global emissions reductions between 2020 and 2035, according to the Environmental Defense Fund. The aim is that for every tonne of CO2 that is emitted somewhere, another tonne is captured elsewhere. In theory, that means that this exchange should balance out and in return prevent an overall increase in emissions (if all human activity is covered by the scheme). Businesses that run climate mitigation projects, such as planting trees or building wind farms will be able to sell the emission reductions to countries. Projects that aim at stopping deforestation or preventing land degradation are examples of effective emissions trading that could lead to greater investment, and in return lead to affordable emission reduction. According to McKinsey & Company, these types of nature-based solutions could account for 65% to 85% of total supply potential by 2030.

But as it turns out, it has proven extremely challenging to establish an effective global carbon market. For almost 30 years, countries have tried and failed to draw rules, until the 2015 Paris Agreement. Even after that, there was still no firm consensus on how to do it, and the countries went back and forth continuously.

But as it turns out, it has proven extremely challenging to establish an effective global carbon market. For almost 30 years, countries have tried and failed to draw rules, until the 2015 Paris Agreement. Even after that, there was still no firm consensus on how to do it, and the countries went back and forth continuously.

Since the countries still couldn’t agree on any robust rules or guarantee that the carbon market will lead to actual emission reductions, some said that it could do more harm than good, and could potentially provide loopholes for polluters to jump through.

According to Time magazine, many environmentalists feared the risk of so-called “double-counting” of emissions reductions if the rules were not written clearly. What is “double-counting”? It is when countries that have reduced their carbon emissions by one metric ton through a solar-power scheme may be tempted to both, sell a reduction credit to another country whilst counting the reduction in their own target. That would amount to half as much CO2 being reduced compared to what the countries claim.

Another big concern was that there were some countries that wanted to be able to carry over old credits that were created under the Kyoto protocol. The Kyoto protocol was established by the UN back in 1997, and it had the first global scheme known as the Clean Development Mechanism: the first carbon market that came into operation in 2006. After the demand for the Kyoto credits vanished, billions of potential credits went unsold. The emission reduction projects that generated them continued and were often unchecked when it came to their effectiveness. Countries that host those projects wanted to be able to use or sell those credits under the Paris Agreement, which sparked a lot of opposition from others.

The consensus came with the COP26 summit taking place in Glasgow in 2021, which resulted in a cleared rulebook for international cooperation in regard to carbon markets. Even with that, many still argue that in the end, the credits bought in carbon markets are just a distraction from the fundamental need for all countries to lay off fossil fuels.

So what do we do then?

The ongoing debates before the COP26 summit did not stop companies and countries from moving forward. In 2021, the voluntary carbon market has seen an exponential growth, going into $1 billion in transactions. The compliance carbon market, discussed before, is where a certain number of carbon credits – per company and per year and the companies must fulfil them. Voluntary carbon markets on the other hand are neither legally mandated nor enforced. That means that organizations/individuals (farmers) with operations that generate carbon offsets, can issue, and sell them to companies/individuals who want to measurably decrease the amount of CO2 they emit.

Voluntary Carbon Markets mean that not only the big polluters can reduce the number of emissions, but so can individuals. There is a plethora of companies, startups and organizations that offer carbon offsetting, available with just a few clicks on the website or in a mobile app. The most common option is the before-mentioned nature-based assets!

According to Sifted, soon nature-based assets could be the “only” game when it comes to the voluntary carbon markets.

It’s true that net zero can only be achieved once every company’s emissions have been cut as much as possible, and residual emissions and corresponding amount of greenhouse gases are removed from the atmosphere. But voluntary carbon markets are a great incentive for smaller companies, startups, and individuals to take action into their own hands and help to stop the rampant climate crisis.

As mentioned before, when it comes to carbon offsetting and nature assets, there is plenty of startups to choose from. To namedrop just a few of them, Klima offers an incredibly easy-to-use app where one can see their own carbon footprint and offset it with a few different projects to choose from. Ecotree has a few forestry and biodiversity projects, and so does Single.Earth with their token system.

Conclusion

With climate awareness and urgency for disruptive action to save the environment, carbon markets might be what governments and industries need to get on track with sustainability goals. Although it needs to be remembered that fundamentally, all countries need to lay off fossil fuels, carbon markets can provide a monetary incentive to not pollute the planet. With voluntary carbon markets growing, now the individuals can also participate in that action, even if the biggest responsibility should still fall on corporations. More and more customers put increasingly bigger pressure on companies to have ambitious climate goals and stick to them, and carbon markets could help with that.

With the growth of the market, there might be a higher demand for skilled GreenTech professionals. That’s where Storm4 comes in! As specialist GreenTech recruiters, we can help you with sourcing the right people for your business. Don’t hesitate to get in touch in case you’re looking for a growth partner in your journey to greener tomorrow!